A Note from the Site Administrator & Translator

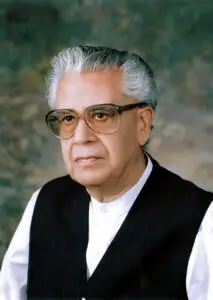

Son of Syed Athar Hussain Zaidi

This autobiographical narrative has been lovingly and faithfully translated from the original Urdu as found in my father’s authored book, Sarv-e-Chiraghan. Great care has been taken not only to translate the words, but to preserve the spirit, emotional cadence, and cultural nuance with which Syed Athar Hussain Zaidi wrote.

If any errors or oversights are noticed in translation, please do not hesitate to reach out to us at admin@atharzaidi.com — your feedback is deeply appreciated.

Where the author alludes to events, individuals, or historical moments that may pique further curiosity, a numbered and starred reference system has been included. You will find explanatory notes and contextual clarifications at the end of the work for deeper understanding.

Please note that this is a work in progress and the format or presentation may evolve as we continue to refine and expand this project.

With gratitude for your time and interest,

— Syed Muddassar Zaidi

1

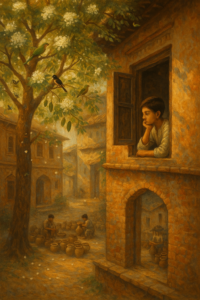

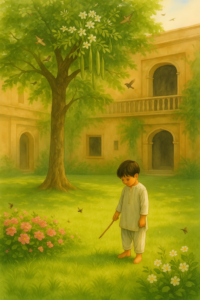

When I crossed the threshold of childhood forgetfulness and stepped into the conscious age of adolescence, I found myself in a small earthly paradise—one whose sweet memory still fills my heart with joy and delight to this day.

This earthly paradise was a beautiful two-storey brick haveli in the Aman neighborhood of my ancestral town, Bharatpur, India. It was the private residence of our small five-member family—myself, my parents, and my two younger sisters. In its courtyard stood a tall Sarjoona (Moringa) tree, whose branches swung with clusters of white blossoms and hung with green pods. Bumblebees and colorful birds fluttered constantly around it. The soft fragrance of the flowers would fill every corner of the house, and the humming of the bees and chirping of the birds kept us, its dwellers, from ever feeling the stillness of the building.

Though every corner of this earthly haven evoked a soothing sense of solitude, my favorite spot was a room on the upper floor, whose back faced the potters’ quarter. I would sit for hours at the window of that room, watching the potters at their craft.

With such delicate skill, they shaped curves into those unbaked clay pots.

As the gentle touch of the hand tool met the soft surface of the clay, a faint, subtle sound would emerge—so soft, yet so rhythmic in its repetition, that it would turn into a soothing melody. This gentle rhythm would float into the stillness of my room like soft waves of music, and I would remain wrapped in its calm embrace for a long, long time.

2

Pottery, in itself a complete creative act, bears a profound resemblance to the intricate weave and process of poetry.

Just as a specific kind of smooth, moist clay forms the essential base of pottery, so too a naturally sensitive temperament forms the core of poetry. On the spinning wheel, as the potter shapes vessels from the wet clay, so does a poet, revolving around the axis of his own mind, draw from a vast reservoir of words and meanings to craft lines of verse like vibrant garlands of imagery. It is said that Khalil ibn Ahmad Basri, a master musician and poet, once passed through the potters’ bazaar in Basra. As he heard the rhythmic sounds of shaping and etching on the clay vessels, their melodic resonance inspired in him the idea of creating poetic meters to measure verse—thus was born the science of ‘Ilm al-‘Arūḍ (prosody).

In the solitude of that room, I had one living companion—a beautiful dove with an earthy hue who had made her nest in one of the ventilators.

Unknowingly, a bond of affection had formed between us.

She would sit quietly in her nest, gazing at me with innocent eyes, while I, outwardly oblivious, remained immersed in the scene of the potters at work.

She was unafraid of me, and I had grown familiar with her presence.

Every now and then, she would lift her neck and release her gentle coo, turning the silence into waves of tender joy. Then, all of a sudden, she would spring into flight and glide into the open sky. A little while later, she would return to her home in the ventilator, cast a fleeting glance at me, fold her wings, and settle quietly into her nest once more. This was her daily ritual—a sight my eyes never tired of beholding.

3

The bond of friendship between me and that dove was, in truth, born out of the peace and serenity that enveloped that room.

The innocent bird, living in such a calm atmosphere and observing my quiet demeanor, had come to trust that neither she nor her nest was in any danger from my presence.

Today, we consider the dove a symbol of peace, but it only builds its nest where fear and terror have no dwelling. In those corners of the world where the serpents of destruction and unrest have, with their venomous hiss of hatred, terrified the dove of peace and destroyed her nest—she has sworn never to return and has taken flight forever.

My ancestral town, Bharatpur, was unparalleled in beauty.

Its grandeur lay in its towering fort, twelve elephant-sized gates, enchanting palaces of rare craftsmanship, the vast moat surrounding the fort, with its ghats for bathing and washing clothes, its lush parks and gardens, permanent exhibition grounds, game reserves teeming with wild animals and aquatic birds—all of which made it renowned throughout India.

But from a human perspective, what was most noteworthy was the city’s peaceful and friendly atmosphere.

People of all religions had, for generations, lived in harmony. Bharatpur had always been a cradle of peace and mutual respect.

Here, people shared in each other’s joys and sorrows alike.

Never had there been any Hindu-Muslim strife. Despite being a Hindu-ruled state, Muslims enjoyed full religious freedom and had equal opportunities in education, business, and employment.

In fact, except for a few positions, most state offices were held by Muslims.

The Hindu majority was largely engaged in trade and agriculture, while Muslim officials were known for their honesty and sense of justice, earning them respect and trust across communities.

They held a distinguished place in the realm of education as well. One such esteemed Muslim scholar was Syed Zaheerul Hasan Jafri, our neighbor, who authored the history of Bharatpur State in Urdu after deep research and painstaking effort.

His work was included as a textbook in the state’s schools. He also preserved the genealogies of all the Syed families of the state in a formally authenticated document. Our family’s genealogy was also preserved with him.

4

The princely state of Bharatpur, once a part of Rajputana (now Rajasthan), was among the twenty-two princely states of the region—relatively small in area. It was founded centuries ago by a Hindu Jat ruler, Maharaja Suraj Mal, who made Bharatpur his capital.

His descendants ruled this state for generations. Though they often stood in defiance against the mighty Mughal emperors, they always embraced their Muslim subjects with warmth and inclusion. These rulers upheld the noble principles of governance, showing respect toward the religious beliefs of others. They made it a point to acquaint themselves with the core tenets of all religions and treated people of every faith with equity and justice. It was precisely this fairness that kept their state free from discord; neither their own people nor outsiders ever rebelled against them. So impartial were their ways that when the Maharaja had a grand Hindu temple built in the city, he also commissioned the construction of a magnificent Jamia Masjid, designed as a faithful replica of the famous Mughal Jamia Masjid in Delhi.

In addition, a vast Eidgah was built on the outskirts of the city, where Eid prayers were offered each year with great splendor and reverence.

The evenings of Bharatpur may not have rivaled the famed twilight of Oudh, but its mornings were certainly no less divine than the dawn of Benares. At daybreak, a halo of light would wrap the city in its golden embrace. The gentle scent of flowers lingered in every alley and courtyard. The dew-kissed breeze, like a whispering guest, would knock softly on the doors, and a wave of cool air slipping through windows reminded the sleepers that morning had arrived.

At the break of dawn, the call to prayer from the mosques and recitation of the Qur’an from Muslim homes would echo alongside the chants of puja from Hindu homes and temples, filling hearts and minds with a profound sense of sanctity. The air was heavy with the fragrance of oudh and amber, drifting from settlement to settlement. Beyond the city walls, along the canal’s edge, stretched vast forests, beneath whose trees one could often behold peacocks dancing in their vibrant splendor, while the melodious calls of the koel filled the morning stillness. As the light grew stronger, groups of schoolchildren could be seen walking in small, cheerful clusters along the road outside the city—making their way toward their schools with quiet determination.

5

The prayer recited at school was about ten to fifteen lines long, written in elegantly penned Urdu — much like a modern-day prose poem. It contained words in praise of the Creator of the universe and a humble plea for His blessings upon the earth. The beauty of this prayer lay in its choice of language; hearing it, no follower of any faith would feel that it represented only one particular religion.

After the morning devotions, the city would come alive in a unique bustle. Though most of the businesses were run by Hindus, Muslims also had shops at every level in the marketplace. However, the highest sales, regardless of the shopkeeper’s faith, were always at those shops where honest dealings and fair pricing were the guiding principles — and this was the true measure of competition.

Essential daily goods were always available in abundance throughout the state. This was because it was legally prohibited to transport staples — like pure ghee, grains, lentils, vegetables, spices, and other household necessities — beyond the state’s borders. As a result of this abundance, prices remained remarkably low. Even those with modest incomes lived with ease, dignity, and little worry. They were able to save something for difficult times, weddings, or festivals. There was no excess of wealth — and perhaps that is why life was so simple and easy.

The deep connection between Hindus and Muslims was also clearly visible during weddings and festivals. Participation of friends from both communities in marriage ceremonies was not just common — it was indispensable. Feasts were thoughtfully prepared with dishes that everyone could enjoy without any religious or dietary objections. One of the most beloved items was patal — an assortment of sweets, puris, kachoris, vegetables, and fritters beautifully arranged on large banana leaves — served in Hindu weddings. In Muslim weddings, various meatless dishes were prepared with equal care.

In houses where wedding celebrations were held, the sound of shehnai and nobat (traditional musical instruments) would evoke a strange blend of joy and sorrow. Joy, because a new home was being established; and sorrow, because a daughter was parting from her father’s home. There is no other instrument quite like the shehnai that can blend joy and sorrow into such a soul-stirring harmony.

6

Hindus and Muslims celebrated each other’s festivals with equal enthusiasm and warmth. On Eid and Bakra Eid, when Muslims would return from offering prayers at the Eidgah, their Hindu friends and neighbors would embrace them along the way and offer heartfelt greetings. In the same spirit, on Diwali, Muslims would extend their best wishes to Hindu friends, often taking their children along to witness the dazzling display of lights in Hindu neighborhoods and to personally congratulate friends and acquaintances.

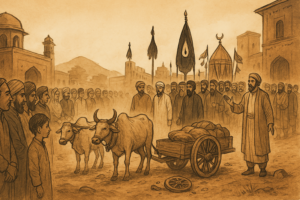

Holi, in particular, was celebrated by the state with official pomp and grandeur. During the day, the Maharaja himself would emerge from his palace in regal splendor, mounted on a majestic elephant, ready to play with colors alongside his subjects. Behind him would follow a grand procession of nobles and officials, riding elephants and horses. Tankers filled with colored water trailed the Maharaja, and through long hoses, he would spray vibrant hues on the cheering crowds. People would gather in throngs—lining the streets, rooftops, and shopfronts—joyously spraying back with water guns and throwing colors on the procession.

However, as the royal parade passed through Muslim neighborhoods, the throwing of colors and powders would respectfully cease. Muslim men and children would welcome the Maharaja and his entourage, showering them with rose petals in a gesture of joy and reverence. In return, the Maharaja would sprinkle rosewater upon them, join his palms with a warm smile, and offer his respectful greetings. He would also ensure, as a mark of deep respect, that no color or powder stained the walls, courtyard, or ablution pool of the grand mosque. His nobles and attendants would follow his example.

This harmony and mutual respect were the hallmark of our city. It was this atmosphere of love and unity that played a crucial role in shaping my character in those early years—instilling in me a deep sense of kindness and goodwill towards people of all faiths. And indeed, this spirit of compassion and virtuous conduct towards others lies at the very heart of Islam’s teachings and philosophy.

7

In that city, there existed no schism between Muslims of Shia and Sunni beliefs. They were bound by kinship, and many inter-sect marriages had been solemnized. The month of Muharram was observed with deep reverence and unity by both communities. In every alley, stalls of milk and sweet sherbet were set up. Offerings and charity flowed freely, cauldrons of haleem were prepared and generously distributed, and in the Imambargahs, trained orators from Lucknow recited the majalis (religious gatherings).

These zakireen were well-versed in history, wisdom, philosophy, modern sciences, and jurisprudence. Their speech—so eloquent, as if it were molded from the heavenly waters of Tasneem and Kawthar—would enchant the ears. Masters of rhetoric, when they ascended the pulpit, they opened entire chapters on justice, martyrdom, and historical themes. And they delivered their recitations with such pathos and heartfelt sorrow that even the most stoic of hearts would be moved to tears.

At times, marsiyas of Anis and Dabeer would be recited, or a local poet would present his own composition in a rhythmic, classical recitation. New structures of expression, inventive imagery, and novel words were heard—phrases that, through repetition and reflection, would gradually unveil their depth and meaning to the mind and heart. Unknowingly, these freshly heard expressions and their meanings became a part of our everyday speech, and our ability to comprehend poetry matured. In truth, these gatherings became profound schools for language, intellect, and learning.

Soz khwani—the elegiac chanting—also held a special place in these majalis. It had a tone all its own, a unique melodic form. I would listen to it with great attentiveness, memorizing each verse, and then in the solitude of my room, I would rehearse them in the same cadence, pouring my voice into those mournful tunes.

Even today, I remember two lines from a famous elegy:

عابد کو جب یزید سے بابا کا سر ملا

سر کیا ملا کہ مرہم زخم جگر ملا

8

When the memorized verses would come to an end, I would begin crafting my own lines and continue reciting soz for a long time. At that age, I had no awareness whatsoever that nature had gifted me with a poetic temperament.

The truth is, the art of poetry cannot truly be taught in any school—it is a form of expression that one is born with, rooted deep in the soul.

On the day of Ashura, when the processions of taziyas, alams, and zuljanah, accompanied by mourning groups, passed through the streets of the city, even non-Muslims would respectfully shut down their businesses and shops.

They would stand solemnly on either side of the road, hands placed over their hearts, heads bowed in silent reverence.

One particularly remarkable moment would come when the procession reached the last square of the city.

There, a Hindu orator—speaking in pure, poetic Hindi and in his own distinct accent—would deliver a deeply reasoned and eloquent tribute on the noble character of the Imam Mazloom (the Oppressed Imam) and the philosophy of martyrdom.

Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and Christians would all gather in a respectful circle, listening in complete silence, their focus and attention unwavering, honoring every word.

Hearing the story of this monumental sacrifice from the lips of a non-Muslim—and witnessing such heartfelt engagement from people of all faiths—deepened the belief that Imam Hussain was not just the martyr of Islam, but a universal symbol of resistance and righteousness.

His sacrifice, made on the banks of the Euphrates with a handful of oppressed family members and loyal companions, against a vast and ruthless army, was a message for all of humanity—that there are battles that can be won not by the sword, but by unwavering truth and supreme sacrifice.

Our own lineage traces back to Imam Zain-ul-Abideen.

Our revered ancestors had migrated from Iran to India in pursuit of livelihood and became associated with the Mughal court in Delhi.

This relationship continued for some time until the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb. Due to some disobedience, they fell out of royal favor and were issued a decree of exile from Delhi. Under imperial orders, they—along with their families, attendants, and belongings—were loaded onto bullock carts and wagons and dispatched under the watchful eyes of Mughal officers, with the instruction that they would be settled wherever the wheel of a cart broke.

After a long and difficult journey, when this exiled caravan reached the borders of the princely state of Bharatpur, one of the cart wheels broke. The Mughal officials, fulfilling their command, declared: “This is now your home.”

And so, temporarily pitching their tents there, the family later purchased land from the local residents within the borders of Bharatpur and founded a new settlement.

9

They named it Syedpur. Over time, the name Syedpur gradually evolved in the local tongue into Sadpura, and to this day, the place still bears that name on the map of existence. In the beginning, our ancestors took up farming in Syedpur, and to expand their livelihood, they purchased more land in the nearby region of Bayana. But finding that the temperament of the land did not quite resonate with their own, they eventually entrusted both the farmlands and the residences in Syedpur and Bayana to tenant farmers under a sharecropping arrangement and chose instead to make Bharatpur city their permanent abode.

With their knowledge and experience, they once again earned positions of respect and responsibility within the state administration.

Generations passed, and by the time I arrived in this world, I saw traces of my forefathers’ legacy in Bharatpur’s Mohalla Aman:

— four old, solidly built ancestral homes,

— a vast, open courtyard,

— and our own residence—a stately two-storey haveli.

The four houses stood silent and abandoned, with moss and age having claimed their rooftops and walls. The wide open space in front had become a playground for children and young men of the neighborhood.

Among our inherited treasures were also ancient manuscripts and books in Persian and Urdu, covering subjects like law, medicine, philosophy, religion, and literature.

Many were handwritten volumes—calligraphic treasures—carefully preserved from termites, bound in thick, protective covers.

Through those books, I was able to glean the pursuits, values, and livelihoods of those who came before me.

My great-grandfather, Syed Tahawar Hussain Zaidi, had a deep interest in religious scholarship and Islamic jurisprudence.

He frequently engaged in theological debates and participated in scholarly dialogues. People of those times stood firmly by their word and promises. True to this legacy, when my great-grandfather once lost a public religious debate, he honored the pledge he had made to his opponent—a promise that our family continues to uphold to this very day.

10

My grandfather, Syed Sadiq Hussain Zaidi, was the only son of his father. He had only one sister. So when my grandfather passed away in the prime of his youth, it was his sister—my grand-aunt—who raised my father, Syed Abid Hussain Zaidi.

Since my grand-uncle was childless, and my father too was the only child of his parents, his childhood and adolescence were spent under great affection and care.

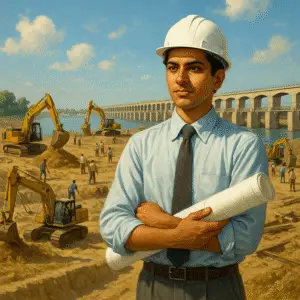

He was nurtured with immense love, and grew up under close supervision. He pursued civil engineering from Lucknow.

But after the early deaths of both his father and his uncle, the responsibility of managing the family estate fell squarely on his shoulders. For this reason, he did not join state service. However, owing to his standing in society and his education, the State Government honored him with a position on the jury panel of the royal court.

Whether it is the blessing of a saint’s prayer or a curious coincidence, for several generations in our family, the firstborn has always been a son—and yet, alongside this, the early demise of the family patriarchs has meant the family has steadily grown smaller. So, when I came into awareness, I had already been deprived of the warm companionship of a grandfather, uncle, or elder male relative. That is why our four ancestral houses in Bharatpur’s neighborhood remained desolate and still. My father was the first elder in our family to live to the age of seventy, and I myself—an only son—have also, by the grace of Allah, now reached seventy. And what a mercy it is that I have been blessed with virtuous and kind-hearted children and grandchildren.

As a child, being the only male heir, I was raised in an environment of utmost protection and care, lest any harm befall me.

That is why I wasn’t enrolled in school at a young age.

I had no cousins to play with either, and so, solitude seeped deeply into my being from the earliest days. Even today, in this later stage of life, solitude remains my most cherished companion, and I find joy in its presence. I prefer the quiet of solitude over the clamor of company—and this seclusion greatly nurtures the world of imagination, which is essential for a poet.

11

Since I was not enrolled in school at an early age, a private tutor was arranged at home to teach me Urdu, English, and Arithmetic. I quickly gained a basic grasp of these subjects, and so, during moments of leisure and solitude, I would turn to the Urdu books available in the house. My reading list included Alif Laila, Fasana-e-Ajaib, as well as marsiyas, nauhas, salaams, and manqabats.

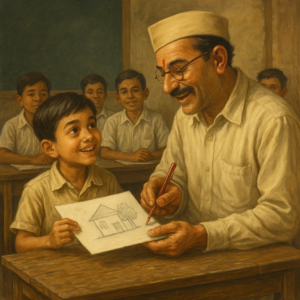

Eventually, when I was admitted to the first (primary) class at school—at a relatively older age—not only was I older than my classmates, but also ahead of them academically. At the state-run school, both Hindu and Muslim teachers taught their students without bias or discrimination, and they always encouraged those who showed promise.

Since I had already begun my education at home, every six months, when a Hindu Education Inspector came for evaluations, he would find me considerably older and significantly more advanced than my classmates. So, he would promote me one grade ahead during each of his visits. In this way, I was able to make up six years’ worth of academic delay in just three, thanks entirely to the fairness and kindness of that Hindu inspector. And thus, a Muslim child was saved from losing several precious years of education.

I can never forget the justice, sincerity, and affection of another Hindu teacher—my drawing instructor. During the annual exam in the fourth grade, the drawing paper carried 50 marks, and the duration was an hour and a half. I completed a clean and detailed drawing within fifteen or twenty minutes and submitted it. The teacher was so pleased, he asked me in front of the whole class, “How many marks shall I give you?” Thinking he was joking, I stayed quiet.

He repeated the question, so I nervously asked for thirty-two (32) marks, which, in my mind, was already quite generous.

He smiled, gave me thirty-two out of fifty right then and there, signed the paper, and said:

“If you had asked for all fifty, I would have given them to you.”

12

Later on, that teacher never awarded more than twenty-five (25) marks to any student in drawing, thereby clearly maintaining the distinction he had made that day.

The promotion and standard of Urdu language education in this Hindu-ruled state can be gauged from the fact that, in the school’s annual prize distribution ceremony, when I passed the third grade with distinction, I was awarded a set of Urdu books—including the short stories of Premchand.

The poems recited at the annual school function also reflected the spirit of harmony between Hindus and Muslims.

One such moment remains etched in memory—when a melodious Muslim student would recite this famous couplet in a voice full of rhythm and emotion:

تو رام کہے میں رحیم کہوں

دونوں کی غرض اللہ سے ہے

“You say Raam, I say Rahim—

We both are calling out to the same Allah.”

And the eyes of the audience would glisten with tears of deep emotion and unity.

Every year, during the spring season, an All-India Exhibition was officially organized on the outskirts of the city.

A permanent exhibition ground, built next to the city’s western gate—Buland Darwaza—included a large open field designated specifically for this grand event.

Traders from far-off cities like Madras, Calcutta, Delhi, Bombay, Ambala, and Amritsar would arrive to promote and sell their goods through colorful stalls.

At the same time, circus groups, theatre troupes, and fairground entertainers from all over India would gather—adding charm and festivity to the exhibition, much to the delight of the townspeople.

Merchants of Bharatpur, belonging to every community, also set up stalls at the exhibition. It became not only a cultural highlight but also a source of respectable income.

From the inner regions of the state, villagers would bring their cattle and livestock for trade, enjoy the sights of the exhibition, explore the city, and then return home—carrying stories and impressions of the vibrant world they had just witnessed.

13

In the open exhibition grounds, annual sports competitions were held, in which school students and young men from the city would participate—and which the townspeople watched with great interest.

It is worth noting that in these competitions, Muslim students and youth most often emerged victorious, and they would be honored with awards and gifts from the Maharaja himself.

During the final days of the exhibition, in the same field, a grand poetic gathering (mushaira) would be held at night under a large pavilion, presided over by the Maharaja himself.

In the bright lights of the beautifully decorated canopy, poets would sit in a respectful semi-circle on stage, while the Maharaja took the central seat as president of the gathering.

A ceremonial lamp would be placed before each poet in turn, and they would recite their verses—either melodiously or in rhythmic prose.

The Maharaja would remain seated until dawn, listening to every poet with full attention, and only after the last poet had recited, would he announce the conclusion of the gathering.

Afterward, all poets were presented with gifts and certificates of honor.

This was a vessel sailing over boundless seas of love.

We all carried in our hearts the warmth of affection and sincerity, and our minds shimmered with the colors of peace and harmony’s rainbow.

And then, the unthinkable happened.

It was a morning in early 1947, and I was on my way to school, when I noticed something for the very first time:

green crescent flags fluttering atop a few Muslim homes.

Until then, the state had known no political activity whatsoever.

This was the first step—a stone cast into the calm blue lake of peace, creating ripples of unrest.

For the first time, the alleyways and neighborhoods echoed with a new slogan:

“We will take Pakistan, no matter what!”

The city’s wise and elderly—both Hindus and Muslims—began to look concerned.

Where once the air was filled with the fragrance of mutual affection, now the monsters of mistrust had begun to dance.

And our hearts were in turmoil.

What was happening?

Why was it happening?

Hindus were now asking Muslims:

“Why are you chanting for Pakistan?”

“Pakistan is not going to be created here!”

“And even if it is, what will you gain from it?”

“Won’t you still live in this city, in this Hindu state, in this India?”

The questions were simple, and the answers were just as simple.

But the people of the princely states had no right to vote.

So, on what grounds were these slogans—“We will take Pakistan”—being raised at all?

14

This was beyond the understanding of boys my age.

A fog of fear had descended upon the city, wrapping it in its eerie embrace.

The very alleys where I once played hide-and-seek with my friends under moonlit nights now appeared haunted, even in broad daylight.

On the 14th of August, 1947, the trumpet of freedom may have sounded, but for us, it came as a warning bell.

Why speak of unfamiliar neighborhoods—even our own lanes and byways now felt foreign.

At school, Hindu classmates began to avoid speaking to me.

And when they did speak, it was laced with accusation:

“You created Pakistan—you betrayed India.”

I will never forget the morning of 16th September 1947.

As I stepped out of the house to go to school, the entire atmosphere felt hushed, desolate—as if the streets themselves were whispering to me:

“Look closely, child… take it all in… for tomorrow, you may never see these lanes again.”

The school too felt different—muted, heavy, unfamiliar.

When I returned home, my parents were waiting anxiously.

I learned that groups of armed Hindu Jats and Gujjars were gathering on the outskirts of the city, preparing to attack Muslim neighborhoods.

It was decided—we had to leave the city immediately.

At the door, a carriage stood ready.

My mother was hurriedly packing away jewelry, cash, and property papers.

Lunch had been prepared—but who had the heart to eat?

The danger was growing with every passing moment.

We had to leave this city—our city—at once.

Suddenly, a thought struck me—my companion dove.

I ran up the stairs to the room.

As I burst through the door, she flinched, startled by my sudden entrance, and stared at me with wide, questioning eyes.

Tears welled up in my own.

“Farewell, my companion… farewell,” I whispered silently in my heart.

I waved to her one last time, then turned and quietly walked back downstairs.

As I stepped out the door for the final time, I cast one long, aching glance at the walls and corners of my earthly paradise.

From the Sarjoona tree, clusters of white flowers swayed sorrowfully, as if waving their own farewell.

We were leaving behind this well-tended, lovingly adorned home—forever.

O God, may no one’s home—friend or foe—ever be emptied like this.

15

This wound still burns like a festering sore, even after all these years.

The pain we felt as we left our home, as we parted from that city—only those who have endured such a tragedy can truly understand it.

The anguish of migration is so overwhelming, may God never subject anyone to such a trial.

During Partition, Muslims migrated only from those parts of India where riots had broken out or where their lives and property were under threat.

Otherwise, no one leaves the land of their birth by choice.

After we left Bharatpur, the homes of Muslims were plundered. Even the doors and flooring were torn away.

Our first stop on this journey of exile was Agra—my maternal hometown.

As a child, I often spent my summer vacations there, returning with memories of visits to the Taj Mahal and joyful moments with childhood friends.

But this time, a shadow of sorrow loomed over me.

We weren’t returning home—we were heading toward an unknown destination.

From one side, refugees from Pakistan were arriving, and from the other, Muslim migrants from India were departing.

A historic exchange of populations was underway.

Roads and railways were no longer safe.

Caravans were being attacked, and trains were being halted, with massacres carried out in broad daylight. Those destined to migrate were being tested once again by fate. Considering these dangers, the decision was made: we would travel by sea.

And so, we journeyed by train from Agra to Bombay (now Mumbai)—a safer route at the time.

Thus, Bombay became the second major stop in our migration.

Soon after, we boarded the ship ‘Kara Para’, heading toward Karachi, carrying with it hundreds of souls—all fellow migrants of fate.

It was a bright morning on 10th November, 1947, when the shores of Karachi became visible from the deck of the ship.

Kara Para moved slowly toward the harbor, and a strange mixture of excitement and emotion surged through the passengers.

The land now before our eyes was the very soil for which we had left everything behind in India.

16

We were entering a new homeland, one created in the name of which we had been compelled to leave our ancestral home.

The ship anchored.

We took our first steps on the soil of Pakistan.

A new country, a new city, and new faces were welcoming us.

Before us lay the long, uncertain journey of our future life.

In Karachi, the Hindu population was vacating their properties and migrating to India.

Large buildings stood empty.

An acquaintance of my father handed him the key to a two-storey abandoned building in Ramswami, and said:

“Go ahead and take possession.

Later, this will be allotted to you in exchange for the property you’ve left behind in India.”

But my father—a man of deeply sensitive temperament—returned the key with gratitude and said:

“Brother, I have already left behind my well-loved home in India with a heavy heart.

Surely, the owner of this building must have walked away from it weeping, compelled by circumstances.

How could I live here with peace in my heart?”

My father was not happy after coming to Pakistan.

The changing social environment and new values of life disheartened him.

Once, when I suggested that he obtain a copy of our family genealogy from Zahir Hasan Sahib of Bharatpur—who too had migrated to Karachi—he replied with deep sorrow: “Son, in this new country, it is not lineage that will matter—it is status and wealth.

Who here will care about ancestry?” And later, his words proved true—exactly, word for word.

Meanwhile, caravans of migrants from India were pouring into Sindh via Bombay, Tharparkar, and other routes.

The people of Sindh, with hearts wide open, embraced them with kindness and helped settle them in Karachi and towns across the interior of Sindh.

Once again, a new chapter of love and loyalty between Ansar and Muhajir was being written—just like the first time in Medina, when the original Ansars had welcomed the Prophet’s companions with open arms.

17

The warmth and kindness shown by the people of Sindh toward the migrants is a luminous chapter in history—one that can neither be forgotten nor its debt repaid.

It was a great journey of love, continuing in this new homeland that had just come into being.

In Karachi, people of vision were building new settlements.

The city was rapidly expanding in all directions.

In schools, teachers were educating students about the birth of Pakistan and the need to strengthen and build it.

They would say, “Pakistan has now come into existence—it is your responsibility to lead it toward progress.”

“There is a shortage of experts in this new nation. You must fill this gap.

Through education, you must rise to become doctors, engineers, pilots, scientists, mathematicians, architects.

You must lead in every field of life.”

Their words had such power and sincerity that each student would begin to imagine a beautiful vision of their future.

I too began to see myself in my dreams—as a civil engineer of tomorrow.

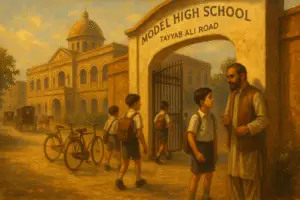

At that time, I was a student of Model High School, located on Tayyab Ali Road in Karachi.

The teachers there were highly capable and taught with great dedication.

One in particular—our Urdu and Persian teacher, Soz Kathwarvi, who was also a poet—taught with such passion that his lessons would settle deep in the mind.

It was due to his care and encouragement that my interest in Urdu and Persian grew, and it was he who nurtured my love for reading and writing.

He would read my essays—on various topics in Urdu and Persian—with great attention, offer thoughtful critiques, and give valuable suggestions for improvement.

Because of my literary inclination, I began by writing adapted stories from English into Urdu for newspapers.

Later, I wrote original short stories and poems, which were published in both literary and semi-literary magazines.

That was a time when a galaxy of unmatched poets and writers was illuminating the literary skies of both India and Pakistan.

Never before—and perhaps never since—have so many towering names of literature coexisted in the same era.

Particularly, the Progressive Writers’ Movement had elevated Urdu literature to remarkable heights, ushering in a golden age of literary expression.

18

During that era, the literary works that emerged shattered the old spell of romanticized, escapist literature.

The focus of literature had shifted—now, it was centered on human beings and the economic and social realities that surrounded them, along with an earnest quest for solutions.

This movement of realism left a profound impact on students of all disciplines, whether they belonged to the sciences or the arts.

I too was deeply influenced by this wave.

Thus, the short stories and poems I wrote during that time bear the mark of this influence.

A few of the poems included in this book are mementos from my student days.

The writers and poets whose works I devoured during that period included Premchand, Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai, Sajjad Haider Yaldram, Krishan Chander, Shaukat Thanvi, Ismat Chughtai, Qurratulain Hyder, Saadat Hasan Manto, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Ali Sardar Jafri, Sahir Ludhianvi, Josh Malihabadi, Fani Badayuni, Jigar Moradabadi, Jan Nisar Akhtar, Firaq Gorakhpuri, Ahmad Nadeem Qasmi—and many others of their stature, whose names would only lengthen this list.

At that time, high-quality literary magazines such as Adab-e-Latif, Sawera, Afkar, Saqi, Naqoosh, and Mah-e-Nau were published regularly.

Students like myself, who nurtured a literary passion, would spend our meager allowances buying these journals instead of other luxuries.

Radio Pakistan’s poetry gatherings, All-India and Pakistan mushairas, literary societies’ sessions, and small one-anna libraries scattered across every settlement—all provided nourishment for the literary soul of the people and students alike.

My intense love for Urdu literature, however, was beginning to pull me away from my academic pursuits.

My dear friend, Abdul Rauf Urooj—a well-known, sharp-witted poet whose lyrical compositions were broadcast from Radio Pakistan—was a man of great sincerity and affection.

In the evenings, we would meet at an Iranian café near Lasbela Chowk, and sit for hours, immersed in discussions about literature and poetry.

He would often counsel me earnestly:

“First focus on your education. Complete your dream of becoming an engineer. Literature will always be there—you can return to it later.”

He would cite examples of many renowned writers and poets who, despite their fame, lived lives of poverty and financial hardship—a warning for those who lost sight of practical realities in their passion for art.

19

Even when I reflected on Abdul Rauf Urooj Sahib’s personal life, I could not help but feel a deep sorrow.

Despite being a talented poet and a fine human being, he was living a life of hardship and financial struggle.

One day, I sat down to ponder over my own future.

What would literature truly bring me?

Even if I managed to make a name for myself in the world of poetry and writing, would it secure the economic future of myself and my loved ones?

The answer was a painful no.

That very day, I made a solemn vow to myself:

Until I had achieved the fulfillment of the dreams I had seen for my future, I would firmly close the chapter of literature within my heart and mind.

After completing my Matriculation from Model High School, I succeeded in securing admission into D.J. Science College, Karachi for F.Sc., which was no easy feat.

Following my Intermediate in Science, I faced yet another daunting challenge:

for admission into N.E.D. Engineering College, there were only ten seats available for Karachi students, while three hundred and fifty candidates were competing.

I sat for the entrance examination—and by Allah’s grace, I ranked seventh among the top ten selected candidates.

Thus, I crossed the difficult threshold into engineering college.

In time, I completed my graduation in Civil Engineering, and at last, I realized the dream I had carried for so long.

Throughout my years of study, I remained abstinent from writing, staying true to the pledge I had made.

Yet, though I distanced myself from composing poetry, the delight of wandering in the realm of verse never truly left me.

Whenever I read or heard a good couplet, I would carefully record it in my diary.

In this way, hundreds of beautiful verses found their place in my collection, and my bond with poetry remained quietly alive.

Even today, a few of those treasured couplets are still fresh in my memory:

الہی موت نہ آئے تباہ حالی میں

یہ نام ہو گا غم روز گار سہہ نہ سکے

Ilahi maut na aaye tabah-haali mein

Yeh naam hoga gham-e-rozgaar seh na sakay

بہت مشکل ہے دنیا کا سنورنا

تری زلفوں کے پیچ و خم نہیں ہیں

Bohat mushkil hai duniya ka sanwarna

Teri zulfon ke paich-o-kham nahin hain

20

ترک مے ہی سمجھ اسے ناصح

اتنی پی ہے کہ پی نہیں جاتی

Tark-e-may hi samajh ise naasih

Itni pee hai ke pee nahin jaati

زمانہ بڑے شوق سے سن رہا تھا

ہمیں سو گئے داستاں کہتے کہتے

Zamana bade shauq se sun raha tha

Humein so gaye daastan kehte kehte

جہل خرد نے دن یہ دکھائے

گھٹ گئے انساں بڑھ گئے ساۓ

Jehal-e-khirad ne din yeh dikhaye

Ghat gaye insaan, barh gaye saaye

فانی ہم تو جیتے جی وہ میت ہیں بے گور و کفن

غربت جس کو راس نہ آئی اور وطن بھی چھوٹ گیا

Faani hum to jeete ji woh mayyat hain be gor o kafan

Ghurabat jis ko raas na aayi aur watan bhi chhoot gaya

کیا کرے گا کوئی دنیا میں وفا ایک سے ایک

دل کے دوحرف ہیں وہ بھی ہیں جدا ایک سے ایک

Kya karega koi duniya mein wafa ek se ek

Dil ke do harf hain, woh bhi hain juda ek se ek

After completing my graduation, I secured my first job as an Assistant Engineer with the Karachi Municipal Corporation.

However, despite working there for six months, I did not gain any significant or notable experience, as there were no major projects underway.

Eager to work on a substantial and meaningful project, I resigned from that position and took up employment at the Guddu Barrage Project near Kashmore.

At that time, it was the largest and most important irrigation project in Sindh, where work continued around the clock in three shifts.

By working day and night, I gained immense practical experience in engineering works and, just as importantly, developed a strong sense of self-confidence.

It was also here that I had the opportunity to understand and connect with the local people—an experience that proved invaluable in shaping both my professional and personal growth.

21

The land of Sindh is the Gateway to Islam—it is the land of Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai’s love.

The people who live here are extraordinarily kind-hearted and simple.

During my time working here, the respect and affection I received from my officers, colleagues, subordinates, and everyone I met, became a beautiful blend of memories—among the happiest of my life.

My Sindhi engineer boss, Mr. Bhatti, instead of calling me by my full name, would affectionately address me as “Shah Sahib”—a title used in Sindh as a mark of honor and respect for Syeds.

In every corner of Sindh, I was met with immense warmth and hospitality, something I can never forget.

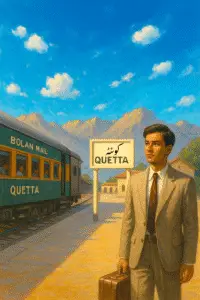

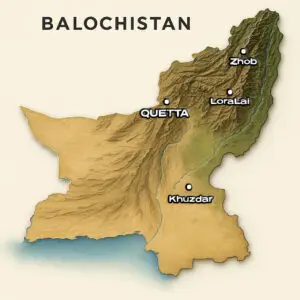

It was due to the extensive experience I gained during my year on this project that I was later selected by the West Pakistan Public Service Commission for the Buildings and Roads Department as an Assistant Engineer, and I was assigned for six months of training in Quetta.

On a bright morning of September 23, 1951, when I arrived at Quetta Railway Station aboard the Bolan Mail,

the deep blue sky stretched overhead like a benevolent canopy, welcoming this stranger.

The bowl-shaped valley was cradled lovingly by mountain ranges on three sides.

At first sight, this small, clean city captured my heart.

When I reported for duty at the department office, the officers, fellow engineers, subordinates, and associates welcomed me with open arms.

Among these sincere and loving people, I immediately felt as if I had found my own.

Quetta’s population was a beautiful mosaic of diverse ethnicities.

Different languages filled the ears with sweetness, and varied cultures delighted the eyes with their grace.

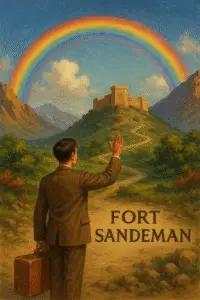

After completing six months of training in Quetta, I received my first formal posting as S.D.O. (Sub-Divisional Officer) in Fort Sandeman (now Zhob).

This town lies about two hundred miles northeast of Quetta.

On May 28, 1952, after a long and exhausting journey, I was entering Fort Sandeman just before evening,

when a light rain had freshly fallen—and the entire town was encircled by a brilliant rainbow.

It felt to me like a divine omen of good fortune.

22

At that time, not even in the wildest corners of my imagination could I have known that the companion of my future journey in life was already living quietly in this very town, unaware of my arrival.

On the morning of May 29, I formally took charge of the subdivision.

The population of Fort Sandeman (now Zhob) was primarily composed of various Pashtun tribes.

They were deeply bound to their traditions and customs—extraordinarily hospitable.

Almost every home had a guesthouse adjoining the main entrance.

According to tribal custom, if a person sought refuge with them, the entire tribe became responsible for their protection.

They were men of their word—in business, no written contracts were necessary; an oral agreement was a bond they honored without fail.

After spending three years in Fort Sandeman, I was transferred successively to Loralai, Quetta, and Khuzdar.

Thus, in a career spanning thirty-five years of service in Balochistan, I was posted to only four stations.

However, due to frequent official tours, I had the opportunity to see almost every inch of Balochistan and, more importantly, to understand its people.

One striking quality I found common across all of Balochistan was that the heart of its ordinary man is as vast as the province itself.

Traditions are honored deeply here.

Major disputes are often settled through tribal councils (jarga) and gatherings (maiterh)—and once a decision is made, it is adhered to with unwavering loyalty.

When I migrated to Pakistan in 1947,

this land and sky were strangers to me.

But the soil of Sindh and Balochistan opened their arms in a loving embrace, adorning me with knowledge and honoring me with livelihood.

The boundless, deep blue sky showered me with blessings.

The people here rained down so much love upon me that it extinguished the harsh, scorching trials of life.

Today, I am a son of the land of Balochistan.

This land and sky are no longer strangers—they are my own.

I salute the compassionate, nurturing soil of my motherland—Sindh and Balochistan.

23

During the course of my career, I remained so deeply engaged with my official duties that the impulse to write poetry remained dormant in the hidden recesses of my mind and heart.

Yet, the flame of passion never truly died; it continued to smolder quietly within.

It’s strange—whenever I was posted away from active field engineering, and found moments of leisure, my poetic instincts would resurface unconsciously, and an impromptu poem or ghazal would find its way into existence.

Verses are like mischievous children—if, at the moment they flash across the mind’s curtain, they are not immediately captured onto paper, they vanish mysteriously, never to be recovered, no matter how hard one tries to recall them.

Thus, whenever verses would descend upon my mind, I would quickly record them in a scrapbook.

Yet, out of caution for potential flaws, I refrained from bringing them into the public eye—waiting instead until I found a true guide, someone thoroughly acquainted with every path and corner of the realm of poetry, someone whose hand I could hold and safely navigate the rugged trails of this art.

The restrictions placed upon my poetic passion during my student years and professional life slowly began to melt away.

As the days of my retirement drew closer, my heart and mind were once again drawn toward poetry.

I thought to myself:

“Now that the bonds of restraint are breaking, why not set this wild steed free?

Why not seek the hand of a master who could illuminate the rough terrain of poetry with the light of understanding and the courage to journey through it?”

And whenever I pondered this, only one name would echo repeatedly in my mind:

the emperor of ghazal, Tabish Dehlvi.

It must have been a pleasant evening in September 1994, when I shared my wish with my brother in law living in Nazimabad, Karachi—that I desired the honor of meeting Tabish Dehlvi Sahib.

He made a phone call.

The response came warmly:

“Come right away.”

A short while later, we were seated face to face with Tabish Sahib at his residence.

24

Before this meeting, I had seen Tabish Sahib many times reciting at televised Naat and Bahaar Mushairas.

I had been deeply impressed by his command over language, his profound poetry, and his distinct style of delivery.

The grip he had over the Urdu language—I have rarely seen such mastery in others. Now he was sitting before me, conversing gently, while I remained silent, trying to absorb the meaning and depth of every word he uttered. It was as though a river of eloquence and brilliance flowed right before my eyes.

I felt acutely aware of my own modest knowledge, and it made me wonder:

“How could the emperor of the kingdom of poetry possibly have time to correct the verses of an amateur like me?” Fearing a refusal, I chose not to reveal the true purpose of my visit, and after sitting there, listening thirstily, I quietly took my leave. Thus ended my first meeting with Tabish Sahib.

After returning to Quetta, some time later, I composed a Naat (a devotional poem in praise of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ).

I shared it with my kind friend, Sarwar Sodai Sahib, who was a producer at PTV Quetta.

He liked it so much that he suggested it be broadcast during Ramadan. However, because Naat poetry is an extremely delicate and sensitive genre, it was necessary that someone with deep insight review it, to ensure there were no errors or oversights.

At that point, there was no choice but to turn once again to Tabish Sahib. Gathering my courage, I telephoned him in Karachi.

He listened to the Naat with great kindness and patience, wrote it down on paper, and asked me to call him the next day.

I realized he did not remember our previous meeting in Karachi.

What amazed me even more was that—even if he had forgotten me—he agreed so easily to help a complete stranger who had simply called him. Surely, this generosity was born of his immense love for the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, which would not allow him to refuse. This selfless and saintly aspect of his nature left a deep and lasting impression on me.

25

The next day, I called him again. He was waiting for my call.

He dictated the corrected Naat to me, and just before ending the conversation, he said a sentence that filled my soul with joy:

“You speak well; continue your practice of poetry.”

These few words were nothing short of a life-giving glad tidings for me.

Upon hearing them, a wave of happiness surged through my veins, and I felt an incredible surge of energy.

This moment of appreciation proved to be the first milestone in my journey of poetry.

Thereafter, a continuous correspondence began between Tabish Sahib and me,

and slowly, the many facets of his poetry and his noble personality began to reveal themselves to me. He is a well-dressed, modest eater, and a person of simple manners. He speaks the truth and appreciates hearing the truth. He abhors pretension and personal praise. His personal life and his poetry are two sides of the same coin—inseparable and reflecting each other. His poetry mirrors his character, and his character gives voice to his poetry.

In my lifetime, I have seen very few individuals whose words and deeds were so perfectly aligned as Tabish Sahib’s.

The first instruction he gave me regarding poetry was that I should deeply study the works of the classical masters,

and understand how they arranged and chose words in their poetry with such elegance. Accordingly, I collected as much of the classical poetry as possible and made it a habit to study them regularly— a habit I continue to this day.

Tabish Sahib had his own unique method when it came to correcting verses.

He made no allowances for mediocrity. Any verse that did not meet the high standards was ruthlessly struck off. When giving feedback on a ghazal, he made sure the verses were well-structured, not fragmented, and that both logic and clarity of expression were not neglected. For verses that could be salvaged, he would subtly polish and guide—but would leave it to the poet to discover the reason behind the corrections himself. This method nurtured the habit of reflection and careful thought in the budding poet, and once he identified his own mistake, he would be less likely to repeat it. It was through this style of correction that I came to understand what “ita’a” (incongruity) was, and how “shutar-gurba” (awkwardness or disjointedness in verse) was corrected.

26

When correcting verses, Tabish Sahib would keep the essence and central thought completely intact,

but with just the substitution of one or two words, he would enhance the beauty of the verse profoundly.

There was a couplet in one of my ghazals:

کبھی مہکے ، کبھی لہراۓ دل میں

وہ بوۓ گل ہے یا موج صبا ہے

Kabhi mahke, kabhi lehraye dil mein

Woh boo-e-gul hai ya mauj-e-saba hai

With his correction, he breathed new life into the couplet by changing just a single word:

کبھی مہکے ، کبھی لہراۓ مجھ میں

وہ بوۓ گل ہے یا موج صبا ہے

Kabhi mahke, kabhi lehraye mujh mein

Woh boo-e-gul hai ya mauj-e-saba hai

(At times it perfumes, at times it sways within me —

Is it the scent of a flower, or a wave of the morning breeze?)

Such perfect, subtle refinement is truly the hallmark of Tabish Sahib’s artistry.

During this journey of practicing poetry, there came a time when I felt overwhelmed and thought that perhaps poetry was not my destiny.

When I expressed my disheartenment to Tabish Sahib, his response was worthy of being inscribed in gold.

He said:

“Neither you nor I are destined to become a Mir or a Ghalib.

Whatever ability God has granted you in this field, be content with it—

and continue your practice of poetry.”

Such was his kindness and humility, that he counted himself and me in the same breath.

Where I am but a speck of dust, and he is a star towering in the heavens!

How can dust compare with the sky?

But he said this to encourage me and fuel my passion.

It was a testament to his greatness and to my own good fortune that I received such guidance.

On another occasion, he told me:

“You have a natural poetic instinct.

Do not burden yourself unnecessarily with the intricacies of meter and prosody.

Just continue your journey of writing poetry.

With time and consistent practice, you yourself will develop the sensitivity to know whether your verses are properly composed or not.”

In literary gatherings, I often mention Hazrat Tabish Dehlvi with the greatest respect and reverence.

27

It is truly a result of my boundless reverence for him—

had it not been for his guidance and support,

I would never have found the courage to present my poetry in literary gatherings.

Just as Allama Iqbal was a devoted disciple of Daagh Dehlvi,

and Hazrat Tabish Dehlvi was a student of Hazrat Fani Badayuni,

they both openly acknowledged their associations—

a clear testament to the sincerity of their reverence.

The letters Tabish Sahib wrote to me while correcting my poetry

are preserved as priceless treasures.

It is my heartfelt wish to publish them,

in Tabish Sahib’s own handwriting and with his permission,

so that young and aspiring poets may benefit from them.

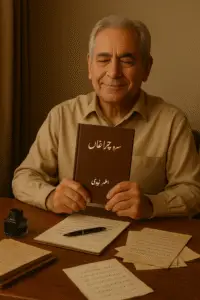

The result of my efforts over the past few years of composing poetry

is now present in the form of “Sarv-e-Chiraghan”.

I began writing poetry seriously only after retiring from my professional career—

whereas most poets, at this stage of life, bid farewell to such endeavors.

All of this is the fruit of Tabish Sahib’s encouragement.

I express my deep and boundless devotion to my esteemed mentor, Hazrat Tabish Dehlvi,

by naming my book “Sarv-e-Chiraghan”,

a title borrowed from one of his own verses.

While writing “محبتوں کا سفر“, (Journey Of Love)

I found it necessary to highlight my past, my ancestral town, and my family background in such detail,

even though such reflections are not usually included in a book of poetry.

The truth is:

I am now at that point in life

where the hand of fate can extinguish the flame of my life at any moment. Given that my time is limited,

and that I likely lack the strength or opportunity to write a separate prose work in the future, I found it wise to weave these memories into this book itself—

thus leaving a record for the new generation.

So they may know:

Who their forefathers were;

what their lineage was;

what livelihoods they pursued;

what their standing in learning and scholarship was;

what their social lives were like;

and what circumstances led them to migrate first from Iran,

then later from India,

to ultimately call a newly born homeland their own.

28

“محبتوں کا سفر” (The Journey of Love)

is a vivid and living scene, spread across the canvas of past and present.

It is not only the story of my own self, but also the chronicle of an entire generation—

a generation that, in the earliest years of life, bore the pain of migration,

that through hard work carved out a place on a new land,

that embraced the newborn state of Pakistan as their sacred homeland,

and fell so deeply in love with it

that at every moment, they strove to offer their body, soul, and wealth in its service.

“The Journey of Love” holds within its lines much more than what appears on the surface.

To truly understand it, it must be compared against the backdrop of today’s times. This journey of life has taught me only one lesson:

Love begets love, and hatred breeds hatred. I firmly believe that the journey of human love will continue eternally. It is another matter that many travelers—including myself—will part ways along the journey, leaving behind sweet and bitter memories, while new travelers will join the caravan. Thus, from one lamp, another lamp will be lit— just like in “Sarv-e-Chiraghan”, where countless lamps glow simultaneously. Even if the fierce winds of time extinguish one lamp,a hundred new lamps light up in its place.

– Athar Zaidi (Quetta, July 23, 2004)

Ah! Tabish Dehlvi

This book was still in the process of publication when September 23, 2004, arrived as a day of deep personal sorrow for me—

the day I was shaken by the devastating news of the passing of my revered mentor, Hazrat Tabish Dehlvi.

My association with my respected teacher had spanned the past ten years.

It was in September 1993, on an evening filled with reverence, that I had the honor of visiting him at his residence in Karachi for the very first time. He received me—a complete stranger—with great warmth and kindness.

From that moment on, his humble and saintly demeanor captured my heart forever.

After returning to Quetta, I remained in contact with him—sometimes through phone calls, sometimes through letters.

This connection continued uninterrupted for a decade. He patiently and attentively corrected my poetry at my request,

enriching me with the subtle mysteries and deeper essence of the art.

From the very first day, it was his gentle nurturing and my own humility that slowly built my self-confidence.

Had I not been blessed with his guidance, I would have surely lost my way on the rugged path of poetry.

He was deeply particular about correct pronunciation and the precise delivery of words.

His thoughtful and meticulous suggestions on my prose and verse were exemplary and written in a manner worthy of emulation.

Born on November 9, 1911,

his long life was a testament to his simple living and noble self-reliance.

He stood peerless in his grace and modest elegance,

wearing simplicity with a quiet dignity. His personality radiated a unique serenity and contentment,

and he always wrote with sincerity, forever filled with a sense of purpose and service to others.

Whenever I visited Karachi, I never missed the opportunity to visit him and seek his blessings.

He would greet me like a kind elder,

and though our meetings were never frequent, they were always filled with meaning and respect.

He held his own esteemed teacher, Hazrat Qazi Badi-uz-Zaman, in the highest regard,

often recalling this couplet of Qazi Sahib, which would flow effortlessly from his lips:

ہر سانس کے ساتھ جا رہا ہوں

میں تیرے قریب آ رہا ہوں

Har saans ke saath ja raha hoon

Main tere qareeb aa raha hoon

(With every breath, I am drawing closer to You.)

And so, Tabish Sahib, too, departed.

With his passing, the last true torchbearer of classical ghazal— that majestic tradition begun by Mir and Ghalib— came to an end forever.

Athar Zaidi

Quetta, October 12, 2004